Birds in the Cage

It was twelfth grade public school AP English class. Mr. D. was one of my favorite teachers. He was old enough to have fully vested his pension, and so any debt he felt toward students was vocational rather than professional. That is to say, he had obviously made the decision not to let disinterested students get in the way of teaching literature.

Mr. D. practiced what pedagogy scholar Michael Bérubé in 2002 would call “teaching to the six.” Suppose you have twenty-five students in a class. Six of them will be totally checked out and helpless. Six of them will be eager, intelligent, and attentive. That leaves a middle thirteen who can be converted either direction. When you teach to the six, you focus your comments, enthusiasm, and expectations on the best students in the class, and in-so-doing you keep their attention and potentially convert some of the middle 13 into the upper echelon.

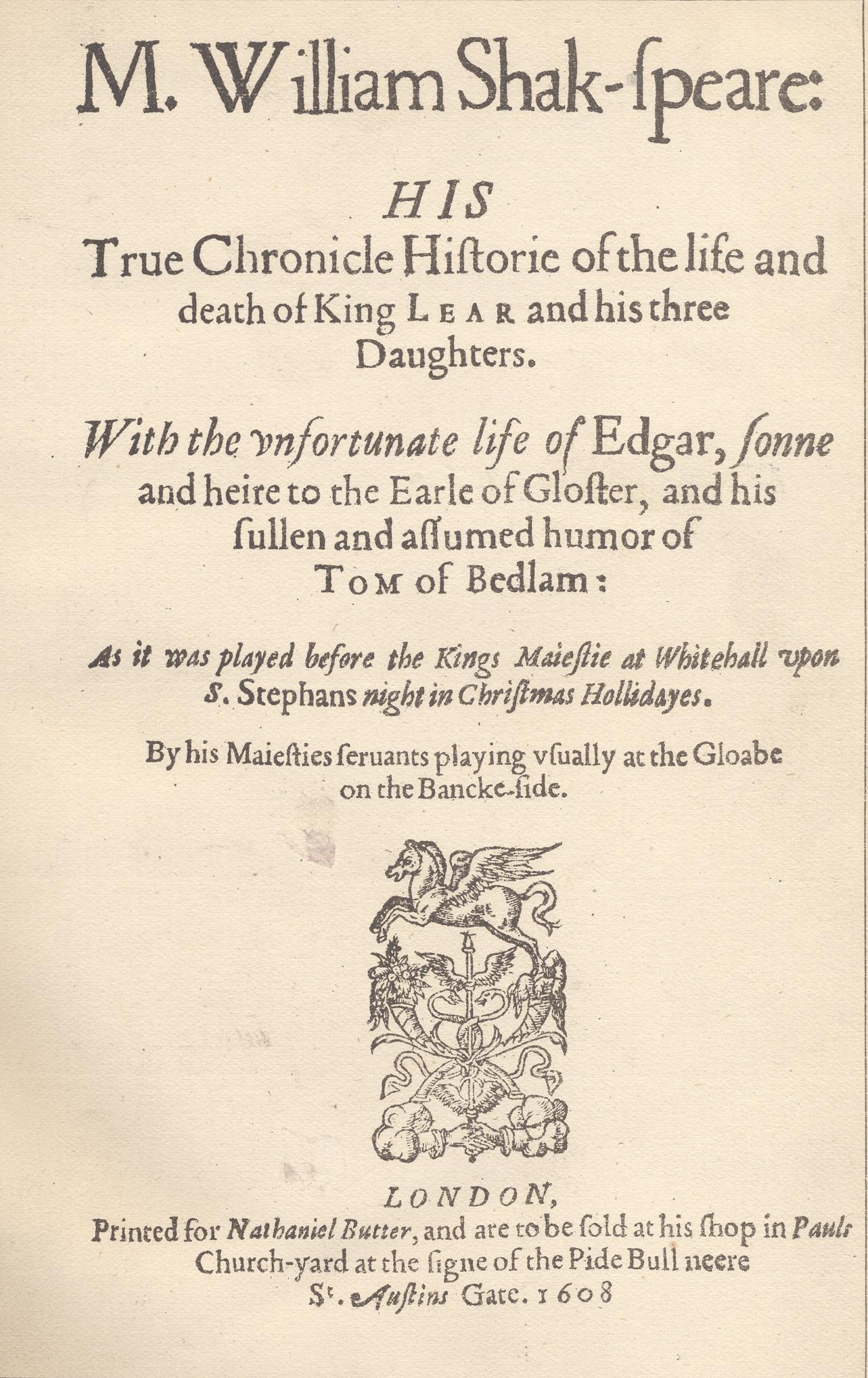

Mr. D. chose to spend his last six or seven years teaching to the students who listened. And so when we read King Lear together, it was the same handful of us volunteering to read the characters’ parts. And we somehow simply lost sight of those bottom six who used the time to space out or doodle (remember those pre-smartphone days when those were the only alternatives?).

I remember reading the part of Edmund who in the second act reveals himself in a soliloquy-prayer to the goddess, Nature.

Thou, nature, art my goddess; to thy law

My services are bound. Wherefore should I

Stand in the plague of custom, and permit

The curiosity of nations to deprive me,

For that I am some twelve or fourteen moon-shines

Lag of a brother? Why bastard? wherefore base?

When I read the lines, my goal was not only to understand them but to be able to paraphrase them, to be able to answer an exam question by explaining that Edmund chooses to worship natural ability, power, and skill instead of honor and piety to one’s family. Shakespeare was like a code, and to understand Shakespeare was to be able to crack the code. So when he wrote some Yoda-esque inverted sentence, like “to thy law / My services are bound,” I learned to reverse the order, switch out the archaic language, plug in the antecedent to the pronoun, and literalize the metaphor. I ended up with something like: “I will take advantage of my natural abilities.” …Beautiful, eh?

But after four years of deciphering Shakespeare, my skepticism got the best of me. And so I approached Mr. D. after class:

“I don’t get it. Why do we celebrate Shakespeare so much in school? I know that he made up words and used a lot of metaphors and wrote a lot of plays. But I don’t feel emotion or experience the poignancy of poetry when I read Shakespeare — certainly not as much when I read Hemingway, Dickinson, or Poe.”

With no disrespect to Mr. D., his reply didn’t convince me. He cited Shakespeare’s importance and influence. The gist was that maybe I’d understand when I studied him more.

Fast forward four years to junior year of college when I enrolled in a month-long intensive course on King Lear. We met for four hours a day, and all we did was read King Lear aloud, slowly, stopping whenever we wanted to for discussion. It was in this patient and seemingly agenda-less context that I first began to experience what it is that makes Shakespeare special.

I read Lear’s final words to Cordelia, attending to their feeling of sacred lightness, and feeling that tragic sadness myself:

We two alone will sing like birds i’ th’ cage.

When thou dost ask me blessing, I’ll kneel down

And ask of thee forgiveness. So we’ll live,

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh

At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues

Talk of court news, and we’ll talk with them too—

Who loses and who wins; who’s in, who’s out—

And take upon ’s the mystery of things,

As if we were God’s spies. And we’ll wear out,

In a walled prison, packs and sects of great ones

That ebb and flow by th’ moon.

How would I possibly crack this like a code? Caged birds singing. Religious rites of absolution. Courtiers like decorated butterflies and the gossip of nobles. The mutable globe spinning around the prison cell, and two holy spies within it.

Not Normal Language

This is not normal language. If you’ve studied Shakespeare, you know he wrote much of his plays in blank verse, which is unrhymed iambic pentameter — ten syllables per line, consisting of ten “feet” or two-syllable units, the first syllable unstressed and the second stressed. It’s said that this rhythm mimics ordinary speech patterns.

I can see it, sort of.

When I was younger I assumed that this is how people spoke in Elizabethan and Jacobean England, with meandering sentences and words twisted toward one another to flex muscles of the linguistic imagination we didn’t know existed. But this was not the case. People did not talk like this in Shakespeare’s time.

So why did Shakespeare write like this? Why are his sentences so compact and lyrical? Why jam together simile after simile? Why make it so difficult to understand?

Stephen Greenblatt, one of the most prolific and influential scholars of Shakespeare living today, speculates that Shakespeare’s aim was to beautify language. Or even more, Shakespeare seeks to elevate the human instrument of speech into an expression of life far above everyday experience. Modern English was young, and compared to Latin, in which all formal texts of theology and state were written, its puerile elegance was still being tested. Shakespeare seems to think through language, not to just fit words to thought, but to generate thoughts by exploring the capabilities of English.

Shakespeare is “teaching to the six,” as it were. Just take a look at Marlowe’s Dido, Queen of Carthage, or Ben Johnson’s Volpone, two of his contemporary playwrights. Their language is graceful and funny and inventive. But anyone who takes the time to look will see in Shakespeare’s plays a relationship to speech that surpasses theirs — not just at the levels of vocabulary and imagery, but an effortless brushwork across the page that reveals depth the more you read it.

Unnatural Words

So don’t struggle with the language. Know that it is intended to transcend one’s normal habits of immediate comprehension. And take your time.

On a few occasions, I had the pleasure of welcoming Shakespeare voice coaches from the Theater Department to my class to give presentations on how to perform Shakespeare. But among the insight they offered, one thing was off. Consistently, folks from the acting department would coach students to deliver Shakespeare’s lines as quickly as possible. If you’ve seen a performance, especially a college performance, you know what I mean. The actors tend to rattle off the lines so fast!

The acting coaches explain this in two ways. First, the plays are long as it is, and speaking quickly speeds things up. And second, they argue that speaking quickly makes the dialogue sound more natural, like everyday speech, and that using a regular pace of speech allows actors to intonate in ways that help express the sense of meaning and assist the audience in understanding what is being said. In essence, the language can be confusing, they say, so speaking quickly and using voice and body motion helps.

The problem, though, is that Shakespeare’s words are not everyday speech. The language is not natural. It’s elevated. It goes beyond the natural into the beautiful, the imaginative, and the intellectual, not brainy but metaphysical.

When reading Shakespeare on our own, don’t rush. Read slowly. I don’t recommend stopping frequently to reread lines that you don’t understand. It is good to reread sections but only after finishing a moment in its entirety because as you pick up on what’s being said and how characters are responding you’re rereading will become more fruitful.

Go with the Flow.

A lovely example of this is the famous in-dialogue sonnet in Romeo and Juliet. As many of you will know, a Shakespearean sonnet is a 14-line lyric poem in iambic pentameter that typically follows a rhyme scheme of ababcdcdefefgg, ending with that couplet of adjoining rhyming lines. While the two are talking, they create a sonnet together.

ROMEO, ⌜taking Juliet’s hand⌝

If I profane with my unworthiest hand

This holy shrine, the gentle sin is this:

My lips, two blushing pilgrims, ready stand

To smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss.JULIET

Good pilgrim, you do wrong your hand too much,

Which mannerly devotion shows in this;

For saints have hands that pilgrims’ hands do touch,

And palm to palm is holy palmers’ kiss.ROMEO

Have not saints lips, and holy palmers too?JULIET

Ay, pilgrim, lips that they must use in prayer.ROMEO

O then, dear saint, let lips do what hands do.

They pray: grant thou, lest faith turn to despair.JULIET

Saints do not move, though grant for prayers’ sake.ROMEO

Then move not while my prayer’s effect I take.

To study this first as a poem is to ruin the experience of the dialogue. Its beauty shines more brightly when it is recognized upon rereading.

And such rereading is the privilege of private reading as opposed to attending a performance. We can go back and experience a moment in a new way. We can look at the assonance and end rhyme visually. We can imagine these lines packed together as a lyric poem. And then we can read them as spoken between the two characters and consider what it means for a sonnet to be created in situ, collectively.

My advice is that our main demeanor in reading Shakespeare should be to read moderately slowly but to go with the flow and only to interrupt your reading to look up vocabulary or track a metaphor once a moment has finished.

Enjoy Yourself

This is not just practical advice. It’s historical and philosophical. In Shakespeare’s time, the principle purpose of dramatic poetry (lumped into the study of what they called “poesy”) was enjoyment. In the first place, poetry delights. In the second, it instructs.

When we study literature at the expense of enjoying it, we denude it of its power to instruct because its power to instruct is primarily by way of our affections. Poetry shapes how we feel toward things. Understanding how it shapes our affections (i.e., poetics) is different from actually having our affections and emotions shaped.

Read with a light heart. There’s no test. Give yourself the freedom to smile when something seems funny or sweet. And for a moment of gravity — like Lear’s “We two alone will sing like birds i’ th’ cage” — allow your countenance to drop a little.

Picture the imagery, but don’t fret over not getting it all. You won’t. And I can’t imagine that Shakespeare expected his audiences to get it all. In fact, I have to think that he hoped that his plays wouldn’t just be watched but read.

Heres a TOC for the series: