I have this funny interest in what adults do between the hours of ~8:30pm and whenever they hit the sack. Maybe it’s just an odd curiosity, but I’ve found that people are often taken a little aback by the question, like nobody had ever asked them that before, or even with a hint of self-consciousness. And having asked dozens of people what they do when work is done, kids (if they’re part of the picture) are doing homework or going to bed, and dinner is cleaned, I’ve come to the conclusion (obvious to most) that the great majority of people spend this period of time watching something on a screen. It’s a combination of smartphones and televisions. And probably this is what makes people self-conscious about it. Not that they should, since most people (often myself included) have the same routine of vegging out with a screen in the evening.

Maybe it’s this old-fashioned idealization of the home, where we think we should be doing something productive or soul-bettering at the end of the day — something like reading Shakespeare.

My follow-up question is to ask what sorts of things they watch. More often than not, the answer is given in terms of a genre. “I’m into real crime shows right now.” Or, “I usually just scroll through funny shorts on my phone.” Or, “I like period dramas.”

Kinds of Story

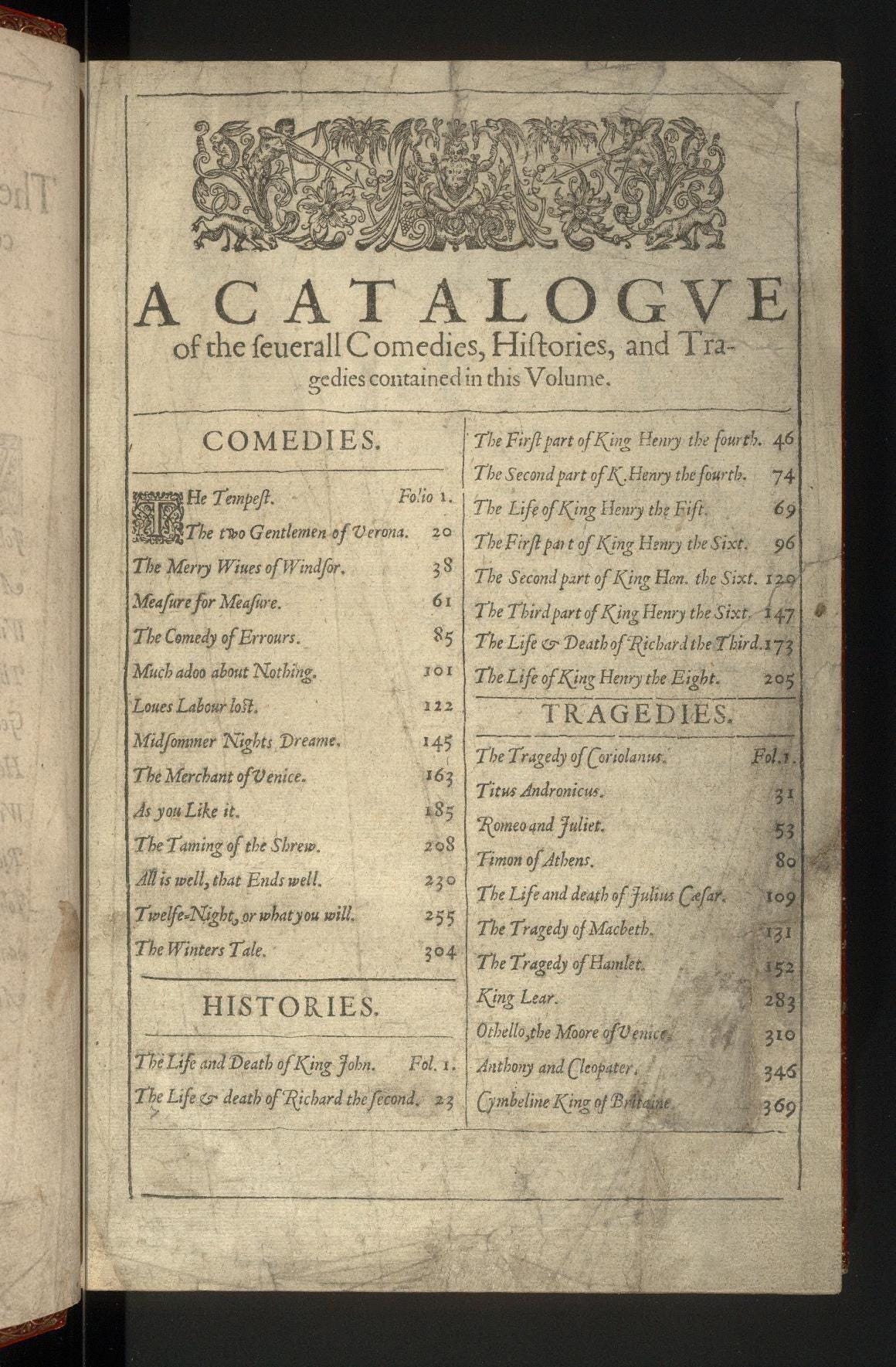

Shakespeare thought and wrote in terms of genres, or types of story. Sometimes this was the difference between lyric poetry as in his sonnets, narrative poetry like in Venus and Adonis, or drama. Those are genres of form. But within these, there are genres of story. The first printed edition of Shakespeare’s complete plays (called the First Folio, in 1623) lists three of them: Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies.

These were the types of genre that Shakespeare inherited from the history of drama. There were others too, like the ill-named “tragicomedy,” a combination of … I’ll leave it to you to guess. And four of the plays he wrote near the end of his career (Cymbeline, Pericles, The Tempest, and The Winter’s Tale) are today called Romances.

Shakespeare didn’t use the word genre. He would have used the word “kind.” An excellent book by Rosalie Colie uncovers how thinking in terms of kinds of story influenced how these stories were created and received. The words we use impact what we use them for. Colie observes that Renaissance authors looked to antiquity for kinds or frameworks that they could not only use but adapt for new purposes.

Genre have lives

When reading Shakespeare, it’s important to understand the basic outline of the genre of play you’re reading because that outline was common knowledge among Renaissance authors and their audiences and readers. A contemporary illustration of this is the new installation in batman films, the 2022 release, The Batman. If a viewer hadn’t seen any of the previous batman movies or any other comic-book movies for that matter, they would fail to understand the meaning to the darkness and realism that this newest film utilizes.

Genres were cultural canvases. They represent a baseline view of the world that authors and playwrights work upon. And we won’t see the significance, much less the beauty, of a play unless we have some familiarity with the expectations that its genre brings to the table.

This brings to mind a related point. Genres contain worldviews.

Genres contain worldviews.

That’s because genres have life to the extent that a culture has the capacity for certain worldviews.

Take tragedy, for instance. Tragedies don’t really exist anymore. They existed in ancient Greece. They continued to be written and performed in ancient Rome. And they experienced a resurgence in Renaissance Europe, especially in England and France. But at some point, they sort of just stopped. Sure, there are modern tragedies, like those of Arthur Miller, and even contemporary art-house tragic plays, but they’re not the same.

People have offered all sorts of explanations for this. Some think that Protestantism produced a sort of spiritual individualism that collapsed the sense of social collectivity upon which the tragic genre worked. Others think that the rise of industrialism in the west strangled the feeling of fate that drives much of the historical tragic genre. Others say that it is religious and ideological pluralism that killed off tragedy. And still others think that tragedy was already dying by the time that Shakespeare began to write them, citing a fundamental incongruence between the Christian belief in the afterlife and tragic inevitability.

But whatever the cause, one thing at least seems conclusive: the form of tragedy does not land very well in modern culture — subcultures, perhaps, but not mainstream cultures. The same is not necessarily the case for comedy today.

This is all the more reason to attend to the genre of the play you are reading. What expectations did audiences come to a performance of a history play with? or a tragedy? or a comedy?

Genre as Cultural Canvas

Studying genre is akin to studying culture. If culture is the complex network of behaviors, norms, and symbolic patterns that empower a people to think or act a certain way, then genres are like blueprints of cultures.

That’s because the driving force of a genre is its logic of cause and effect. How do we account for the end of a story? …through an interpretation of the events that preceded them. More often than not, this entails interpreting the culpability of characters’ actions. How responsible is somebody for the collateral damage of a minor mistake they made? How ambitious is too ambitious? Is our fate written for us, or do we have personal agency? Are forgiveness and reconciliation possible, and if so, how do we achieve them? These are the sorts of cause-and-effect questions that are baked into the genres that Shakespeare inherited and worked with.

Take, for example, the trilogy of plays around King Henry V: Henry IV, parts 1 and 2, and Henry V. Everyone in Shakespeare’s London knew that Prince Hal, as he’s initially known, would eventually assume the throne and become the greater leader, Henry V. It’s a coming-of-age story as much as anything. But what kinds of coming-of-age stories did Shakespeare have to draw from? He had the records of the historian, Raphael Holinshed, who writes from the perspective of one anticipating the triumph of Henry VII and the rise of the Tudors who eventually became Shakespeare’s patrons. But Shakespeare also had the example of Plutarch’s Lives of famous Greek and Roman leaders. He also had access to hagiographical writings (lives of famous saints) as well as contemporary portrayals of great figures by Boccaccio and John Lydgate.

Each of these earlier examples has a different purpose. Some celebrate a person. Some reinforce the validity of a great house or family. Some are works of spiritual devotion. And some, like the Mirror for Magistrates, are intended as exemplar, or patterns for rulers to imitate. And it is composition of these works as genres that give life to these purposes.

In setting out to write a history play, then, Shakespeare had a host of canvases or templates to choose from, each with a different purpose. And this fact allows us to view the authorial decisions he makes with more nuance, meaning, and even emotion. In the case of the Henry IV and Henry V plays, Shakespeare makes several noteworthy additions or deviations. One is the prominence of the character Falstaff, Prince Hal’s debauched but loyal friend. Falstaff comes into new light when you consider that the genres of historical life writing that Shakespeare knew didn’t give nearly as much consideration to the depth of human friendship as Shakespeare chose to create between Hal and Falstaff.

Shakespeare could shape the genre this way because his culture allowed it. In the first place, his culture retained sensibilities of nationalism that made the history play effective. And second, his culture’s view of kingship had the capacity for — even the hunger for — imagining its kings not only as rulers but as real people with intimate and complex friendships.

As I write this post on election day, I consider our own culture. We, by contrast to Elizabethan England, would certainly accommodate the behind-the-curtain portrayal of a ruler’s personal life, but our culture would likely find King Henry’s triumph too derivative and optimistic.

So what do I need to know about these genres?

We get it. knowing more about Shakespeare’s genres makes us better readers of his plays. But what exactly do I need to know about them? Most of us don’t have the time to read academic books (most of which are nearly unreadable) about historical drama.

Fortunately that isn’t necessary. As it turns out, what plays of a certain genre share in common is actually more minimal than you might expect. There are relatively few rules or patterns that they follow. And anyone who has undertaken this study knows that most of the best plays bend these rules anyway.

But there are still certain things we can expect and detect, either in their presence or absence, as we read. When the ghost of Hamlet Sr. appears at the beginning of the play to inform Hamlet Jr. of his murder, we can recognize a convention that dates back especially to the Roman tragedies of Seneca. A ghost appears. It’s unsettled. But that’s not good news. These ghosts are symbols of torment and the conditional imbalance of the world, not to be simply rebalanced by vengeance. Or the setting of a play like Measure for Measure might draw on the ancient tradition of city comedies where characters express themselves against seemingly unjust laws. That connection calls to mind particular patterns through which we expect reconciliation. So when Shakespeare’s play does not proceed that way, we know we’re witnessing an especially intentional decision.

More to come

In the next two posts in this series, I’ll discuss comedy and then tragedy in turn, outlining what I view to be the essential components that readers of Shakespeare would benefit from understanding.

So stay tuned! And subscribe if you aren’t!