We're Out of Control

Frankenstein is having a moment.

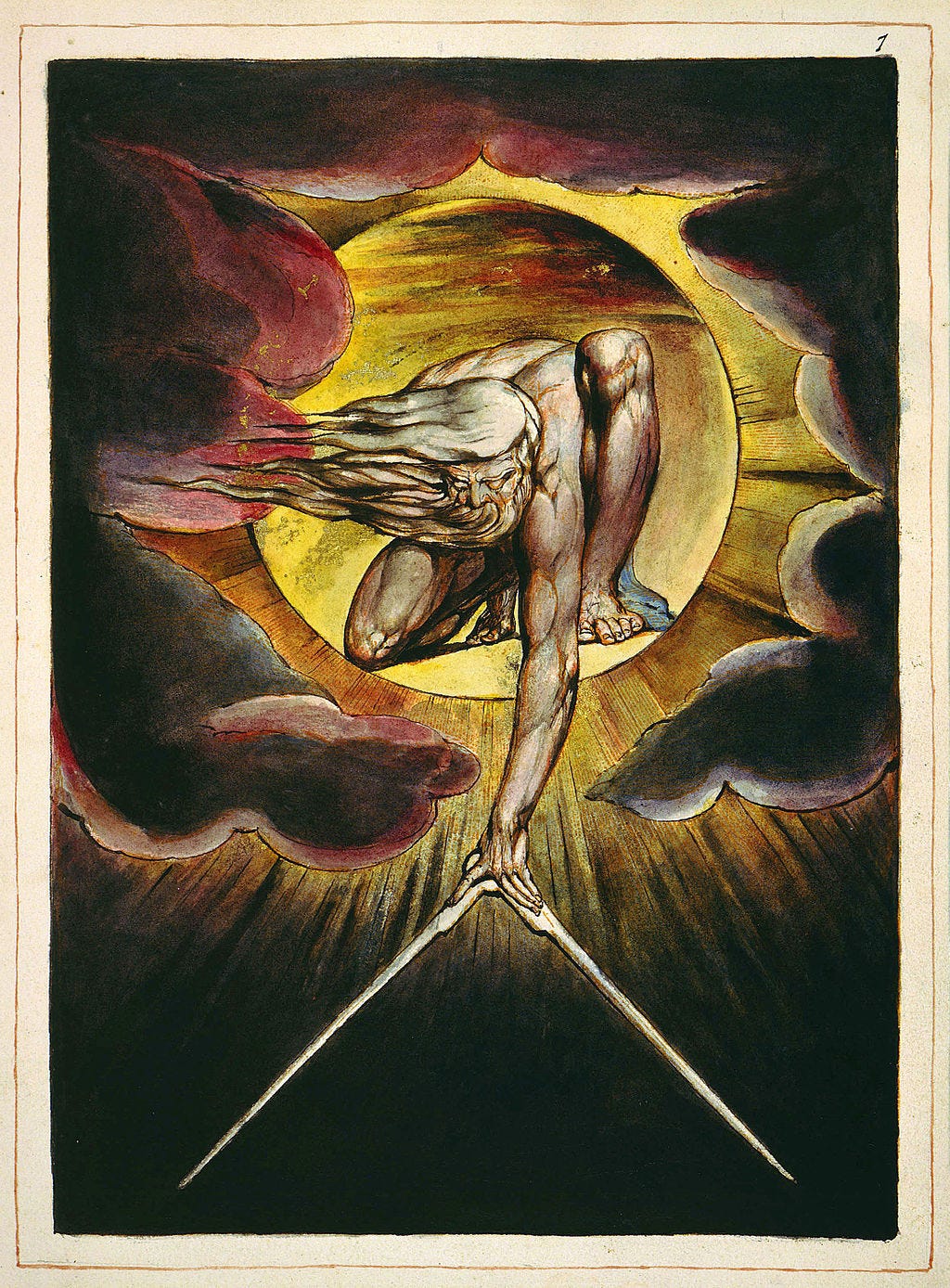

Back when we were recent college grads, I met up with my friend, Aaron, who was excited to show me his new tattoo. He lifted his sleeve, and I immediately recognized it: a muscular figure, perched against the sun, his “hoary locks” waving in the air. The figure, Urizen, reaches down toward the earth and holds out a two-pronged compass, reminding the world that humankind is not boundless. It can be measured. Humanity’s time, its body, its mind can all be circumscribed.

There are three reasons someone would get a tattoo of one of the Romantic poet William Blake’s engraved prints.

They know nothing about the book from which it came but simply like the image.

They’re a member of a metal band.

They’re a poet at heart.

Aaron’s reasons fell into the third category. But don’t be mistaken. Aaron didn’t see this image as a reflection of God’s absolute power or of the limitations of human experience. Just the opposite, like Blake himself, Aaron saw this authoritative figure as a challenge. Urizen’s time-worn beard and hair blow with the wind. He’s an antiquated god, an albatross hanging around humanity’s neck.

Our challenge, as poets and revolutionaries, Blake thought, is to snap his compass, to break out of the false oppositions between good and evil, light and dark, that the old religion imposes, and to discover that inner spark that dwells within each of us — the imagination, a source of energy that burns brighter than any divine law or moral rule.

[ENTER: The Creature]

I thought of Aaron’s tattoo when I noticed that the San Francisco Ballet was coming to town to perform Frankenstein. A Hildegard professor accompanied some students to see it last weekend.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is having a moment. Besides the ballet, Guillermo del Toro has adapted the novel as a Netflix movie debuting November 7th. It’s renewed popularity doesn’t surprise me. We live in an age of new rationalities. And every time I open my email or check my LinkedIn feed, I see a new article or panel on artificial intelligence — in ethics, in education, for businesses, predicting the future.

In addition to a tool and an opportunity, we call AI a “problem” because its advances outpace our understanding of it. The challenges it poses are partly economic (is it stealing our jobs?) but, more importantly, human. How do we maintain our deepest humanity if AI can outperform our minds? And, what responsibilities do we have, as creators of an intelligence that exceeds our own?

Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein as part of a contest among friends. During a vacation, a nearby volcano erupted (ominously enough), forcing the party indoors. Given the famous literary company that included Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, and John Polidori, they challenged one another to write a ghost story. Mary Shelley’s became one of the greatest that we have.

“Playing God?” Not really.

It’s a standard answer students give to the question, Where does Victor Frankenstein go wrong? One shouldn’t “play God,” they say.

But what does that really mean? Does it mean that we ought not to do things that God does? It can’t be that, since people are exhorted to emulate God in so many ways. So maybe it means that we ought not to attempt things that only God can do, like creating life out of inanimate matter. But how do we determine which of God’s activities belong to him alone?

In Shelley’s novel, there are two initial signs that Frankenstein has overstepped his prerogative as a scientist. The first occurs when he’s pursuing his obsessive study into the “life principle.” When the process of pursuing an endeavor causes a person to become less virtuous and less human, then the end of the endeavor itself is probably distorted:

If the study to which you apply yourself has a tendency to weaken your affections, and to destroy your taste for those simple pleasures in which no alloy can possibly mix, then that study is certainly unlawful, that is to say, not befitting the human mind.

And the second occurs when the creature first comes to life. Here’s the Royal Ballet’s depiction of it:

When the San Francisco Ballet performed the scene, the creature’s first movement was to arch its back as it inhaled an enormous breath of air. But within seconds, Frankenstein sees the creature and recoils in terror. He wasn’t horrified when it was just matter stitched together on a laboratory table, but when he sees its living eyes — constantly calling them “dull,” “watery,” and “yellow” — he cannot bear to be in its presence. So Victor flees the laboratory, and in his absence, the creature also flees. And the two don’t reunite until almost a year later.

Whether or not Frankenstein is culpable for playing God, the cause of the creature’s destructive behavior is much simpler. He’s really, really ugly. Victor decided to make it 8-feet tall, for some reason. And he was so fixated on bringing life to the body that he didn’t think about its appearance:

His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes... his shrivelled complexion and straight black lips.

Imagine, had Frankenstein somehow made the creature reasonably beautiful in appearance, then he likely would have assimilated into society; Victor himself may not have abandoned him; he may have found companionship; and his life may have been peaceful.

But it’s an unsettling thought to consider that Victor’s biggest mistake was being a bad aesthetician. Still, this observation changes everything because it offers a glimmer of hope. If nothing else, it suggests that the hard work is done (Frankenstein made life!). Now all he has to do next time is knock a couple feet off the creature’s stature and work on its cosmetics.

But reading the novel this way has huge consequences for how we understand Shelley’s representation of human nature, natural law, and all things nature.

Frankenstein is a Romantic Tragedy — which we no longer accept.

The most surprising change that the ballet adaptation makes to the novel is that Victor Frankenstein kills himself in the end. In the novel, by contrast, he dies slowly, exhausted from chasing the creature across the arctic. It isn’t a suicide.

And this makes all the difference. “Well, he virtually kills himself in the book,” someone might contend. But he doesn’t. He wants to catch the creature, although he knows that he stands little chance of vanquishing it were he to meet it. He even makes Robert Walton, the explorer to whom he tells his story, promise to kill the creature in his stead.

To portray Frankenstein’s death as a suicide is to imagine him as a tragic protagonist. He realizes that he was wrong, and he kills himself under the weight of the curse he’s brought upon the world. Classical tragic figures suffer because they make impossible decisions between two horrible options. The tragic protagonist represents a classical view of the human condition. Humans have “a fixed nature,” as T. E. Hulme puts it. They might think they can transcend it, but they can’t. And when they try to, things become tragic.

But Victor Frankenstein doesn’t fully accept his mistake. Consider the unjust execution of Victor’s family friend — virtually his sister — Justine. She’s falsely convicted of murdering Victor’s young brother, William, and only Victor knows that it was his creature who performed the murder. Although he’s extremely bent out of shape over it, he doesn’t do anything about it. He wants to step forward in court and provide his evidence, but he refuses. And Justine dies. A similar attitude informs Victor’s decision to marry Elizabeth, even though the creature has vowed to kill her on their wedding night — and Victor knows fully well that the creature is capable of keeping his vow.

Frankenstein is in denial of the limits to his nature. He is a Romantic, like Shelley herself. He believes himself to be “an infinite reservoir of possibility,” to have a “limitless nature” (Hulme again).

And that’s why in the novel Victor doesn’t kill himself. Human nature is a curse that he doesn’t quite accept. He recognizes the godlike authority of human nature — like Urizel measuring the world with his compass — but he can’t bring himself to submit to it. Instead, he aestheticizes it. And once it’s alive, he hunts it down as if he’s hunting his own limitations.

But we can never fully escape the classical view of human nature.

Where Frankenstein represents the romantic “hero,” the Prometheus who refuses to accept defeat, the creature itself represents an old way of thinking about the human condition. It knows that its nature is fixed. Specifically, it’s fixed by ugliness. Its personality seems to be amiable, but society rejects its appearance. The creature fulfills Rousseau’s prophecies: society changes the human experience.

Shelley’s mother was the famous feminist, Mary Wollstonecraft, who in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman argued that young women were being deprived of the kind of education they need to grow, not as women, but as humans. In making this argument, she refers to the immortality of the soul. We all believe that souls are immortal, she says. Both men’s souls and women’s souls. And we also believe that the soul’s immorality announces its highest moral obligations — duties not to society but to God and to the universality of humankind. And so we contradict human nature itself when we educate young women in a manner that is bad for their souls.

Mary Shelley inherits this way of thinking and takes it further. Combining this line of thought with Rousseau, she suggests that society too has a soul, but it’s a complicated and fickle kind of soul. And, for the creature, it is corruptive.

Recall the time that the creature spent spying on the French family in their cottage hideout in the Swiss Alps. The family are exiles, and from them the creature learns how to speak and read; he learns about human emotions and family bonds. He reads a copy of Milton’s Paradise Lost that he finds there, and he identifies himself with both the characters of Adam and Satan:

Like Adam, I was apparently united by no link to any other being in existence; but his state was far different from mine in every other respect.

He had come forth from the hands of God a perfect creature, happy and prosperous, guarded by the especial care of his Creator;

he was allowed to converse with, and acquire knowledge from, beings of a superior nature: but I was wretched, helpless, and alone.

Many times I considered Satan as the fitter emblem of my condition; for often, like him, when I viewed the bliss of my protectors, the bitter gall of envy rose within me.

The character doubles in Shelley’s novel are off the charts.

Victor Frankenstein and his Creature

Frankenstein and Robert Walton

The Creature and Adam

The Creature and Satan

Frankenstein and Satan

Frankenstein and God

We can argue with one another all we want about whether the creature has a soul. But whatever we might mean by “soul,” we can agree that it has a mind. It’s an accelerated version of human civilization. And as it turns out, civilization rejects it. The creature is a classical tragic hero. It weighs its options and determines that none of them are good: live a life of misery that it doesn’t deserve, or torment its creator until Frankenstein takes responsibility.

The history of Romantic literature follows the slow realization that the classical vision of life is impossible. That spark of imagination within us that burns brighter than the sun is not, in fact, free from external constraints. And like Shelley, so many great writers attempt to find a way around this fact but end up at a common conclusion. Wordsworth, Emerson, Baudelaire, Melville, Eliot: for each, the Romantic dream of a limitless nature is stifled. And what’s more, it’s typically stifled by something mundane — disease, depression, politics, poverty, … even aesthetic ugliness.

I predict that Frankenstein will continue to grow in new popularity.

…but not for the reasons we might want.

There is a general growing feeling that things are getting out of hand. Technology, politics, global warfare, individual consumerism, violence. What factors feel like they’re still in our control these days?

And which of these factors did we not create ourselves? I hope that what’s driving us errantly forward is simple ambition and laziness of mind. But I fear that the real culprit is that we’re once again in denial of human nature.