In ancient writing, the quest to define the soul tends to focus on what happens when the soul is separated from the body at death.

We have the body. It’s made of parts. It doesn’t move itself but is moved by something else. It decays. And eventually it stops and changes into something else.

And then we have this other thing (in us, as us, with us) that is not made of parts and cannot be divided. It seems to move itself in thought and will. It doesn’t seem to decay and, given that it moves itself, perhaps cannot decay. And so we have reason to think that it doesn’t stop being itself when it is separated from the body. In other words, the soul lives on.

These might not be the traits that come to mind for most of us when we think about the soul — singular, indivisible, self-moving, incorruptible. I imagine we think of a spirit, an inner conscience, or maybe we think of something inside us that has moral worth, or even something like the breath that is breathed into Adam’s body.

Another characteristic of the soul in ancient writing is that it is typically represented as undertaking a journey.

That is to say, the story of the soul is also that of a journey.

And because for the past couple of years I’ve been fixated on the role that Beauty plays in the human experience, I’ve taken notice of the soul’s interaction with Beauty in its journey. The driver in this journey is Beauty, as the soul responds to what it is attracted by. Because the soul is immortal, it possesses the ability to distinguish Beauty. In other words, because objects of attraction have eternal, unchanging, and indivisible Beauty in them, the soul can beautiful itself by interacting with beautiful things.

But the soul faces a problem: sometimes it gets stuck in a beautiful thing, a type of desire we call infatuation, when it loves the thing itself without differentiating its beauty from the rest of it.

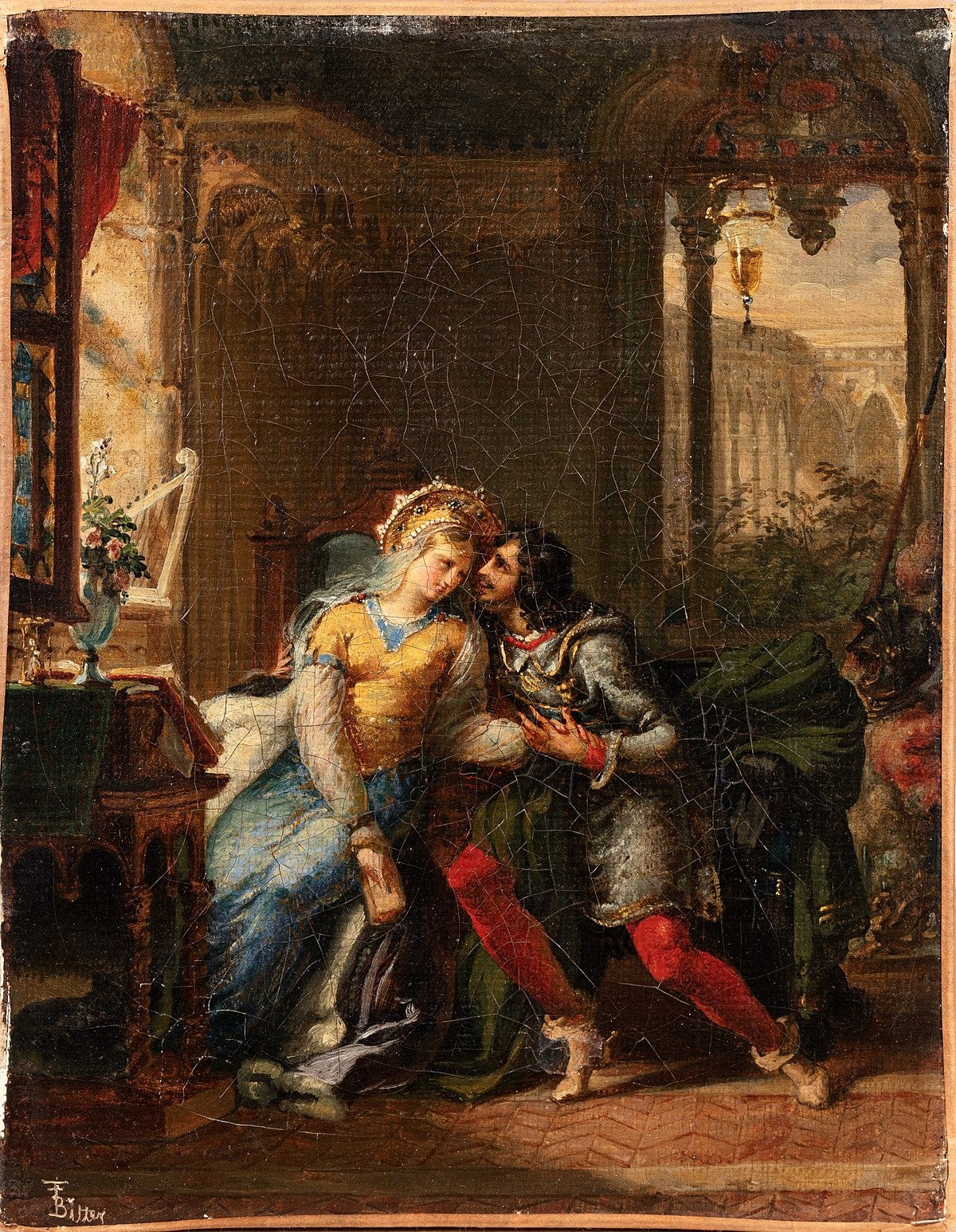

How can a disordered soul prone to desiring what is ugly be expected to respond with a stronger desire for something that is truly beautiful? A teacher of mine in college summarized this as the problem of Lancelot. Lancelot absconds with Queen Guinevere, wife of King Arthur to whom Lancelot has pledged loyalty. Lancelot is utterly in love with Guinevere, who is unequivocally beautiful, as Mallory puts it: “for he loved her out of measure above all other women in the world.”

How then, my teacher asked, can Lancelot overcome his love for Guinevere to do what is right? If only it were as simple as rightly identifying what is beautiful about Guinevere and loving her as a beautiful soul ought to love her! If you think about it, this poses an enormous problem for our understanding of morality. Are humans, by virtue of their attraction to beautiful things, destined to fail? As my teacher put it, “If there’s no way out for Lancelot, then we’re all doomed!”

Plato’s answer—though it is only a partial answer—is to understand and exercise the reciprocal connection between a soul and the beautiful thing that it loves. The soul in the cave needs time for its eyes to adjust to the brightness of the true sun rather than to the light of the fire that casts shadows on the cave wall. It is a process that necessarily involves pain. The third-century Neoplatonic philosopher, Plotinus, imagines the procedure as chiseling ourselves as if we were statues.

Withdraw into yourself and look. And if you do not find yourself beautiful yet, act as does the creator of a statue that is to be made beautiful: he cuts away here, he smoothes there, he makes this line lighter, this other purer, until a lovely face has grown upon his work. So do you also: cut away all that is excessive, straighten all that is crooked, bring light to all that is overcast, labour to make all one glow of beauty and never cease chiselling your statue, until there shall shine out on you from it the godlike splendour of virtue, until you shall see the perfect goodness surely established in the stainless shrine.

Readers of C. S. Lewis will recall Eustace being descaled by Aslan in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader.

Part of the human condition is that you cannot resist what you find beautiful. What can be changed is your power for finding the beautiful. The only hope that Lancelot has is to love something more powerfully than his infatuation for Guinevere. And to accomplish this, Lancelot himself must become more beautiful. An elevated soul illuminates the beautiful in its objects of affection. A refined version of Lancelot would see Guinevere more clearly.

And it is the nature of the soul to see Guinevere more clearly.

The only way forward—or upward—is that the soul itself must become beautiful; it must be shaped in habit so as to love what is truly beautiful more than it loves what is only partially beautiful.

And here we reach a crossroads.

One path is the puritanical one. It concludes that in order to avoid falling victim to base desire we should rid ourselves of the love of beauty altogether. After all, isn’t that the safer path? The Dominican Friar, Jerome Savonarola, preached in Renaissance Florence in favor of the elimination of anything that was aesthetically pleasing. Savonarola led a mass burning of paintings, musical instruments, poetry, cosmetics, and even mirrors in Florence in 1497 that has become known as the Bonfire of the Vanities. The event was an extreme reaction to what Savonarola and others saw as the widespread corruption of the city, but reactive or not, it represents the view that the beautiful appearances of things are simply too strong for Christians to enjoy responsibly. In the decades following the Protestant Reformation in Europe, reformers stripped of their statuary and paintings, whitewashed decorated walls, and destroyed liturgical items made from valuable materials. Iconoclasm, as such events are described, views the human senses and especially the eyes as particularly vulnerable to sin and superstition.

The danger of this path is that it throws the baby out with the bathwater, where in this case the baby is the power of worldly love to elevate the soul to higher forms of affection. Were Lancelot simply to run away as soon as he felt a burning desire for Guinevere, he would not have succumbed to his affair. But by consequence, Lancelot would also abandon the higher calling of his oath to Arthur and chivalry. In other words, arguably he would not have had the chance to become beautiful himself.

The second path is to enter the fray of worldly beauty. What this does not mean is that one puts oneself in compromising situations with fingers crossed that they’ll someone discover true beauty. Instead, on this path we acknowledge that the best things come from what is beautiful and reflectively engage the embattled world of the beautiful.

This second path is one of madness.

But, as Socrates says in the Phaedrus, “the best things we have come from madness,” with the important caveat, “when it is given as a gift of the god.”

Madness is how Plato describes the effect of beauty in the Phaedrus, a book on the shortlist of the most important writings on beauty that we have. In the dialogue, Socrates gives a speech criticizing Love and specifically relationships that are based on the love for another person’s beauty. But he immediately feels ashamed of this speech.

“Don’t you believe that Love is the son of Aphrodite? Isn’t he one of the gods?” he asks Phaedrus. Socrates’ point is that despite its tendency to cause people to lose control of themselves, love is a divine thing and so must at heart be good and desirable. And likewise, beautiful things are holy, in a sense.

Socrates says that they key to understanding that divine madness in the form of love is found in the nature of the soul and its ascent through beauty. He asks Phaedrus to imagine the soul as a chariot driven by a charioteer with a team of two winged horses. One horse is noble and loves “honor and self-control; companion to true glory, he needs no whip, and is guided by verbal commands alone.” The other horse is ugly and “companion to wild boasts and indecency . . . and just barely yields to horsewhip and goad combined.” The team of horses represent the embattled nature of the soul. When the chariot confronts something alluring, the noble horse complies with the charioteer’s self-controlled desire, while the wild horse seeks to consume the object. As a soul, the chariot exists in the realm of divine things where it experiences things as they really are, but eventually it descends to lower realms where it encounters things that are beautiful but less purely so. And if a soul descends even further, then it sheds its wings entirely and is incarnated into a body.

Here, it must strive to ascend back to the realm of the gods. And the way it gets there is through beauty. When the soul encounters a beautiful object, such as a potential lover, the wild horse will forget the true beauty it experienced in heaven and find base uses of the beautiful thing. But in such situations the soul has an opportunity to remember the true nature of beauty and to see it in the beautiful object. When this happens, the places where the wings once were soften and melt, as it were, and new wings begin to grow, ultimately lifting the soul upward.

Both the uplifting and the uncontrolled encounters with beauty are a kind of madness. When the soul confronts something beautiful it is reminded of the true beauty that it once knew, but it “cannot fully grasp what it is.” The experience is one of pain, discontent, and curiosity. As Socrates describes it, the beautiful thing unlocks a memory of the soul’s true nature—that of a self-moving, free, and rational being. And having glimpsed that memory, it voraciously seeks to return to it. That is the phenomenon of love as activated by beauty. Therefore we should not fear lovers, Socrates says, because in his beloved “he has a mirror image of love in him,” which he thinks of as “friendship.”

Lancelot’s problem is that he separated his love of Beauty from his love of Goodness.

And this severance resulted in a weaker soul, a soul that was not acting as it should.

In Socrates’ second speech on the divinity of Love, it is beauty that has the power to elevate the soul—not goodness or truth directly. And Socrates recognizes this important distinction. For the remainder of the dialogue, Socrates turns his attention to rhetoric, the art of speaking. And he argues that the rhetorician must understand the nature of the human soul as well as the truth of the thing that he is speaking about. But even this very combination of understanding the nature of knowing and the thing that is known is driven by the desire for beauty.

Even philosophy, in its highest forms, is an act of love and a call to Beauty: “To call him wise, Phaedrus, seems to me too much, and proper only for a god. To call him wisdom’s lover—a philosopher—or something similar would fit him better and be more seemly.” Just as one cannot know what is true without understanding what it means to know the truth, one cannot recognize the beautiful without being beautiful oneself. The dialogue concludes with Socrates’ prayer to the god, Pan. “O dear Pan and all the other gods of this place, grant that I may be beautiful inside.”