In the words of Hildegard’s marketing director, Kyle, “people want permission to trust their gut.”

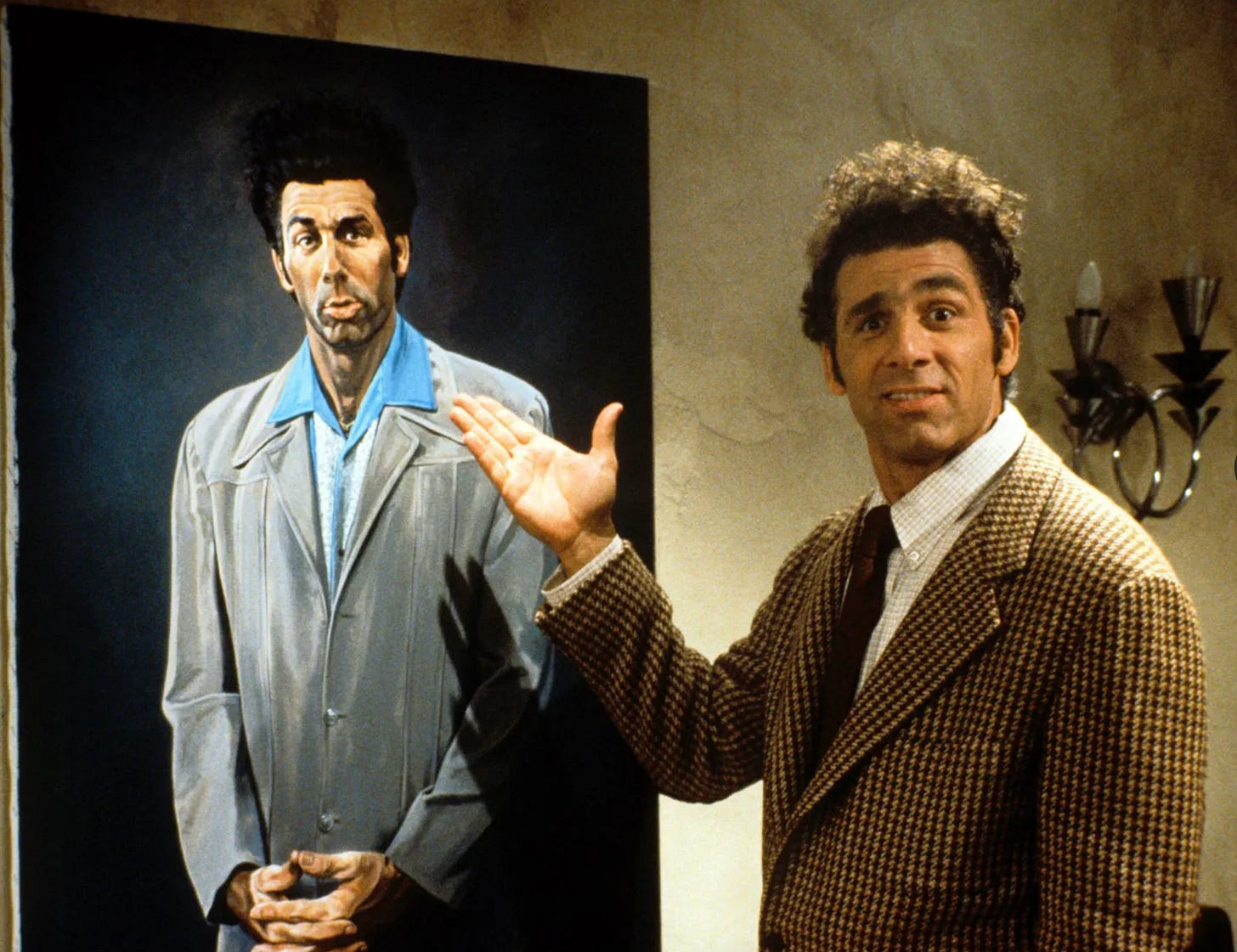

During the year between graduating college and moving across the country for grad school, I worked for a small nonprofit under a newly minted CEO who just loved introducing himself as the “CEO.” He was the sort of boss that would barge through the door, like Kramer, already mid-sentence into his latest articulation of the grand problem we were solving. He’d call the office on a Wednesday and demand military-grade updates from each department as if he were on a 20-minute layover between flights (while we could hear “It’s a small world” ringing in the background and his daughter asking for a churro”).

One day he slapped down a copy of Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink on my desk. “Read this by the end of the week!”

I did read it. But it seemed to me that my boss failed to pay attention to Gladwell’s many warnings about dismissing good people and good information by making snap judgments. Gladwell argues that we can get accurate information by attending to our first impressions of situations and people … as long as we understand that this is superficial information, in the blink of an eye. What he is not advocating for is a hubris of one’s own intuition, the stereotype of the overly confident supervisor. Don’t be like JK Simmons as the newspaper editor in Spider Man.

But that caveat aside, there’s truth to Gladwell’s argument that we can overthink our way into situations that our gut rightly tells us to avoid. So, neither should we be like Jane Austen’s Elinor Dashwood. And I’m fascinating by this phenomenon. As a lifelong student of Shakespeare, I think of those moments in the tragedies just before things really go south. Moments like when King Lear tells his daughters to speak eloquently of their love for him. Or when Hamlet questions the veracity of his father’s ghost by reminding himself that sometimes demons disguise themselves as ghosts to mislead people. Or when Iago uses reverse psychology to plant the seed of suspicion in Othello:

"O, beware, my lord, of jealousy;

It is the green-eyed monster which doth mock

The meat it feeds on."

When these scenes are performed on stage, you bite your upper lip and squeeze in your shoulders with a little cringe. True … you think … but maybe take a step back and trust your first impression.

Sometimes we do need permission to trust our gut. And in my experience, we rationalize away from our gut feelings of things more frequently in unimportant matters than with important ones.

If it seems like something’s up, then something’s up.

When I was in my late 20s, I had a friend who drove too fast. Not go-to-jail fast, but fast enough for me to notice. He drove this partially restored Nissan S30 from the 70s. And when we drove in it, his foot was always slightly too heavy. He’d accelerate toward break lights, take too many yellow-light chances, switch lanes too frequently, turn too acutely. It wasn’t enough for me to say anything, and I never felt in danger. But I took notice.

Let’s call this “consistent somewhat unusual social behavior.”

And like most of us who try to be polite and inclusive, I gave him the benefit of the doubt. That’s what good people do, right? He just likes his car a lot, I thought. Or, it must be a habit from when he was 16 that he never grew out of. It would be too much, I thought, to assume that there was anything more going on. It’s just a quirk.

But one day I was proven wrong. With the usual slightly fast speed, we approached a red light in the left lane where cars where stopped. Seeing the stopped cars in the left lane and perceiving that the right lane had fewer cars in it, he yanked the wheel to the right to switch lanes at the last second. But when he did, the car in the right lane suddenly stopped short and we smacked into the back of it — denting it as well as the front of his beloved Nissan. As things go, it was a minor accident. The woman in the car in front of us was startled but calm-headed. She opened her door, saw what had happened, and pointed to the parking lot at the intersection for us to pull into.

But my friend responded differently.

He got out and stood in front of his car in the road, clawed his hairline with his fingers, and let out a primal shout into the pavement. Refusing to pull into the parking lot, he then approached the woman and began screaming at her. “Look around you when you’re driving!” She tried to disarm the situation and suggested we pull into the parking lot. At this point, drivers in the cars whose paths we were blocking had begun honking their horns and telling us to pull over, as it was only a fender bender. But my friend wouldn’t hear it. He kicked his bumper and screamed again. Then he grabbed the handle of the woman’s door to prevent her from starting her car and pulling to the side. He wanted to have it out then and there. Something had snapped in him. I’d never seen this side of him. It was clearly his fault, but he didn’t see it that way.

Standing in the parking lot a minute or two later, as he continued to rant and wail, I put the pieces together. My friend’s habit of driving too fast was not just a personality quirk. It was symptomatic of something else going on in him, and I was seeing that “something else” in full breath. With the benefit of time, I concluded that his habit of speeding was informed by his understanding that when he’s on the road everybody else should be expected to accommodate him. Of course, this doesn’t make sense. It breaks the universalizable principle — where you cannot universally apply the same mindset or behavior to everyone, otherwise the road would be un-drivable. And even further, I realized that he carried this sense of his own exceptionality into other areas of his life, albeit areas that were mostly harmless.

Rewind 9 months earlier when I first noticed that he drove fast. I gave him the benefit of the doubt. Different strokes for different folks. But I was wrong. He didn’t deserve the benefit of the doubt. Or at least, it wasn’t true that his habit of speeding was only an isolated quirk.

I should have followed the ‘99% rule.’

It’s not a prohibition or law but a rule in the sense that one follows a rule of life, like not trying to exercise at least 3 times a week or not eating fish on Fridays. It’s guiding principle. The 99% Rule says:

If somebody consistently exhibits socially unusual behavior, 99% of the time that behavior is indicative of a greater abnormality under the surface.

Matt Smith’s untrained pop socio-psychology at its best. Why not 100%? …only because that 1% of the time when consistent socially unusual behavior is not indicative of something bigger probably exists, though I haven’t encountered it.

The Rule is counter-intuitive for many of us because we’re trained to give people the benefit of the doubt, to see them charitably. And we should be charitable in our relationships. We don’t know what’s going on in people’s lives. We’ve all got our own crap.

But the point of the 99% Rule isn’t to dismiss people or reject them because they have quirks (as we all do). The point is not to be naive when overlooking might carry risk.

And to be clear, if consistent socially unusual behavior is just the tip of the iceberg 99% of the time, that does not mean that the iceberg beneath the surface is insidious or even significant. I’m not looking for reasons to judge people. And most of the time, the 99% rule applies to innocuous behaviors.

For example, two of my friends tend to leave parties and social gatherings without saying goodbye to anybody — what was called making an “Irish exit” in less culturally sensitive times. You probably know someone who does this too. It’s totally harmless most of the time. Let’s apply the 99% Rule. A habit of leaving parties slightly early without saying goodbye is a consistent socially unusual behavior. And sure enough, it’s symptomatic of something else under the surface — not anything significant, but something real nonetheless. In the case of my friends, it’s related to their general avoidance of conflict. They don’t want to be in a situation where the host says, “So early! Why don’t you stay for 30 more minutes?” Sure, it may be the case that avoiding conflict causes problems elsewhere in their lives.

An example from my own behavior: I don’t like talking about work on the weekends. And if a friend or my in-laws asking me about work on a Sunday, I don’t have a problem saying that I prefer not to talk about work on the weekends. Some of you might think that that’s reasonable, but I recognize that it’s a socially unusual thing to do. And indeed, for me, it’s indicative of a bigger habit of thought and feeling, related to my use of categorizing in order to cope with busyness and stress. I’m a categorizer. When it’s time to do a thing, I focus on that thing. If I think about everything else I need to do, I don’t feel as free to do that thing. Is this a problem? Maybe, but probably not significantly.

The Power of Social Pressure

The word “social” is an essential qualifier in the definition of “consistent socially unusual behaviors.” The reason the 99% Rule applies so consistently is because social norms hold so much power of us. It’s really hard to break social norms consistently.

So hard, in fact, that in order to do it, one of two things needs to be happening. Either you need to have conviction enough to adopt a way of life that is outside the norm, or you need to lack the control to conform.

An example of the first case would be a teenage girl dressing more modestly than most of her peers at school. That’s hard to do, but if it’s informed by a belief system that is stronger than the social pressure to do otherwise, one experiences a power or freedom to break the norm. Sometimes the exception becomes the norm when it is buttressed by a social circle, such as observing a sabbath on Sunday and attending a worship service. That doesn’t break the 99% Rule because it’s normative within the relevant social circle.

The 99% Rule only applies to instances where we lack the control or freedom to conform. This could be the result of coping, or repression, or lack of self-control, or even just an abnormal habit upon which we come to rely.

Here’s an example we can all relate to. You’re at a cafe, and two friends sit down at a table near you, apparently to catch up with one another. But after 30 minutes, you realize that one of them has been doing 95% of the talking. The companion is a patient listener, but that’s not the point. The point is that the first person isn’t just talkative. He or she is apparently under the unjustified impression that their companion is at the cafe mostly to hear them talk. That’s socially unusual. And for the general norm, it’s really difficult to do … unless you’re unaware of the fact that you’re doing it. I’ve sometimes fantasized of walking over and saying something like, “Excuse me, I don’t mean to interrupt, but I just wanted to observe that you’ve been doing almost all of the talking in this conversation and haven’t asked your friend a single question in 90 minutes.” But doing that, of course, would be a violation of the 99% Rule.

How to use the 99% Rule

I wouldn’t blame someone for having the impression that the 99% Rule is judgmental, or insensitive, or projects norms onto people. After all, people are different, right?

But the point of the 99% Rule isn’t to place judgments or to impose norms where variety exists. Most of the time, my applications of the 99% Rule are light-hearted and don’t affect my relationships at all. So he eats his food really really slowly. Probably that’s related to something. Who cares. Or, so she never responds to texts within the first 12 hours of receiving them. That’s certainly socially unusual and either related to a very deliberate decision or to an unintentional coping strategy. But that’s fine. Maybe it’s for the better. Another caveat, of course, is that the 99% Rule doesn’t apply to instances affected by mental or behavioral illness.

So how do you use the 99% Rule?

It’s useful when something’s at stake, big or small. You’re organizing something and need to rely on somebody’s punctuality. You’re thinking about taking a new friend into your confidence. Somebody makes a request on your time, and you’re considering whether to give them 2 hours on a Wednesday. Or you can apply it when considering whether to ask something of somebody. The 99% Rule can help you determine whether that request may be more imposing on a person than it would be on most.

I once interviewed a recent college grad who dressed slightly too casually for the meeting. I wouldn’t go as far as to call this a red flag. But it did break the 99% Rule, specifically as regards this applicant’s apparent understanding of the social situation. I ended up hiring him because I gave him the benefit of the doubt. The position involved writing and social media. And sure enough, he had difficulty understanding the “rhetorical situation” and the expectations of our target audience. Had I applied the 99% Rule, I would have saved 3 months and turnover costs.

The 99% Rule is especially applicable to civic discourse. Have you ever had the experience of being in a group of relative strangers (a class in school, a impromptu gathering a church, a conversation circle at a party, a breakout meeting at work), when an individual makes a political comment that is surprisingly partisan and presumptuous of others’ political views? It could be an overt criticism of Bernie Sanders or an indictment of Donald Trump. The Rule applies both ways. The fact is that we live in such a polarized political climate that the normal attitude to have is one that acknowledges a likely plurality of opinions.

What is “unusual” about someone who sounds off with the implied understanding that of course everyone agrees with them isn’t the taboo of bringing up politics in a casual conversation with mixed company but the apparent assumption that everyone agrees with them. There’s a tonal and contextual implication that no reasonable person would hold a different opinion. That’s a violation of the 99% Rule. And what do we do with this observation? I don’t alienate the person. In fact, I enjoy talking with people who disagree with me. But I do take note not to introduce that person to friends of mine or hold strong political views. I probably wouldn’t hire that person for a role that involves interpersonal interaction. And, depending on the severity of the incident and how consistent that behavior is, I might not admit that person to a course of study.

Does that sound harsh? Maybe. But my own disposition is to call a spade a spade.

There you have it — the 99% Rule.

It essentially amounts to the observation that, If it seems like something’s up, then somethings up.

Try it out. Let me know what you think.

I’m excited to announce that we’re launching online entrepreneurship courses for high school students.

These are self-paced modules in the essentials of entrepreneurial thought — how to build a product, program or service; how to lead an organization; how to identify problems that need solutions . . . taught from a faith-based perspective.

https://www.hildegard.college/entrepreneurship-course

Check it out and joint he waitlist!