I was late to church on Sunday. Or more accurately, I was on time to our church campus, but my wife and I sent the kids in to the service while we sat in the car watching the excruciating long last 10 minutes of the English Carabao League Cup final between Newcastle United and Liverpool FC.

Newcastle were leading 2-1 with just minutes remaining. And Liverpool, the winningest team in the history of English football (soccer, for us) was throwing caution to the wind. The final whistle blew and the camera focused on Newcastle’s captain, the Brazilian central midfielder Bruno Guimarães, kneeling in the grass, bellowing cries of ecstasy into the turf he’d occupied for a hundred minutes. Within seconds, his midfield colleague, the Italian Sandro Tonali (who looks a bit like Kylo Ren) leaps upon Guimarães’s back, giving the field an earful himself. One after another, they dogpiled and shouted and cried and embraced.

The rest is a blur. …and I mean that literally. Newcastle’s uniform is the classic black and white vertical stripes. Tens of thousands of these shirts occupied the stands, and as fans danced in frenzy and waved their striped scarves in the air, it showed on the small screen of my iPhone like a flashing ocean of grey. My wife and I hugged each other embarrassingly in the church parking lot, and I may or may not have wept a bit.

If it isn’t clear, I support Newcastle. We’re few and far between in the States. Most of my friends who are soccer fans support Manchester United or Arsenal or maybe even Manchester City, teams that dominated the league in more recent years. But for roundabout reasons, when I was 16 I chose Newcastle, the “Team of the North,” as I call them. The cup final victory on Sunday ended a 76 year old drought during which Newcastle failed to win a major trophy. It’s akin to the 2004 end of the curse of the Bambino for the Red Sox.

I’m not proud of my actions — watching sports on my phone while my kids are in church, rewatching the post-game celebrations four or five times since then, earnestly explaining to my children that this is a top ten day in my adult life. But that’s the pull that sports have on some people. And my sport is soccer.

A close friend of mine used to tell me that she didn’t like competition.

And I’ve certainly come to question competition and competitive sports in recent years, especially since my kids began playing sports.

Any parent whose kids play youth sports falls into one of two categories. Either the game causes them to utterly lose themselves, or it serves as a rare occasion for reflection. If you’re a parent, then I don’t have to convince you of the former group. Maybe you’re one of them. The things parents say to referees and umpires, the pressure they put on their 9-year-olds, the money they spend on private lessons and camps — it is not exaggeration to say that youth sports literally become the highest priority for many families, even though they would never admit that out loud. The irony, of course, is that folks who research sports development professionally find that there’s either a negligible or even a negative correlation between parents’ financial/emotional investment and a child’s likelihood of making it big in that sport, whatever that means.

The other kind of parent finds himself at the game, hearing the abuse flung at the referee and kids alike, and looking around wondering what in the world we’re doing. But there’s no stopping it. It’s part of our culture. We say that parents live vicariously through their kids, but I think it’s more personal than that. It’s a matter of identity. I am a winner, is really all it comes down to.

Youth sports are a can of worms in themselves. Professional sports is another matter, and I’m unprepared to offer any comprehensive commentary on them — except to say that they’ve always presented a puzzling question to me as a Christian, illustrated in the image of my emotion at Newcastle’s glorious victory while sitting in the church parking lot.

What role does competition have in the lives of Christians?

I make myself a target for even posing the question, I know.

On the one hand, sports have a long history. We think of Sparta and the role that sports played in training athletes who are also soldiers. Or we think of the Roman games and the exploitation of slaves for entertainment. After all, one of the historical meanings of “sport” is “entertainment.” You’d have to be a hard-nosed materialist to think that the Spartan model applies to us today, as if playing sports cultivates the dog-eat-dog mentality that will make you successful in business. But I suppose a Christian might justify this perspective by observing that the kingdom of heaven and the kingdom of earth are different realms and abide by different laws.

Opposed to this is a Christian perspective on what author, Kyle Strobel, has called “the way of the lamb.” This is to emphasize how Jesus’s ministry directly overturns the economy of the world. The rich are poor. The wise are foolish. The winner is really the loser, and vice versa. Interestingly enough, I met Kyle when our daughters were on the same soccer team, competing together. From the perspective of the Beatitudes, what is the value to competition and physical competition in sports in particular? It assumes a zero-sum account of human behavior, and it cultivates attitudes that (maybe) Jesus is telling us to unlearn.

It may be, however, that most of us resonate with neither of these two perspectives — the sports-as-training-for-getting-ahead view, nor the win-by-losing view.

There’s a third option, though, one that I describe as a festive attitude toward sport.

One prototypical example were the Pythian games at Delphi, the ancient “navel” of the world. Delphi is dedicated to Apollo, and if you walk up the meandering path past the temple where, according to Aeschylus, the Furies dwelt for a time, you enter an enormous racing arena that hosted all sorts of sports, including races, javelin throwing, fighting, and equestrian competitions. The Pythian games are just one example of sporting competitions held in honor of the gods, and like several others, in Delphi’s case, they were specifically symbolic of a myth.

Apollo fought a mythical serpent, called Python who controlled the Oracle at Delphi. When Apollo defeated it, he claimed the Oracle as his own. The episode symbolizes, among other things, the transfer of divine power from an older generation of gods who largely disliked humans to a generation who viewed humans as a reflection of themselves.

So the purpose of celebrating the event with sports was to remember and honor the bond between humans and gods, to use physical activity to remind us of the resolution of strife in a new form of piety.

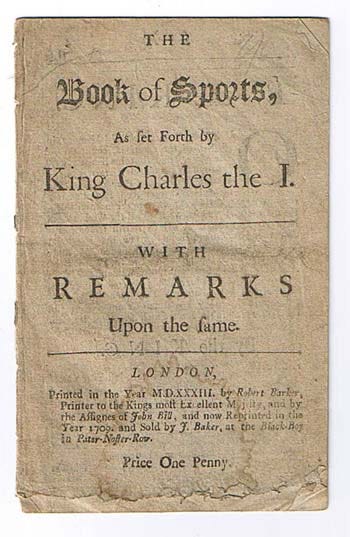

If you’re a reader of this Substack, then you will connect this purpose of sports to what I’ve described as the “festive” nature of dramatic comedy. The festive approach to sports hasn’t always been embraced by Christians, though. In 17th-century England, King James I published a declaration (later republished by his son Charles) called “The Book of Sports” in an attempt to settle a dispute between Puritans and Anglo-Catholics.

The Puritans didn’t want sports performed on the sabbath. The Anglo-Catholics, however, viewed sports as a natural expression of the celebratory orientation that the sabbath brings. It’s important to notice that both sides presented their argument as the properly pious approach. James sided with the Anglo-Catholics, allowing sports and games along with other festivities on the sabbath.

The ultimate question is so complicated that, at least in my opinion, it’s probably not worth dwelling on too much — Is competition good for Christians? But if it is — and I’m prone to think that it is — then I prefer the festive attitude.

Hildegard’s next “Creators & Coffee” is coming up this Friday, March 21. I love these events. They’re short (just 1 hour). And they provide an opportunity to meet other creators and to hear a bit about somebody’s story.

This time around, Hildegard faculty member, Jeff Tanner, will be talking about the “dream statement,” the grand vision for society that drives an organization’s mission. He’ll share his own experience creating these and how he uses them to guide organizational strategy.

More info here: https://www.hildegard.college/workshops/creators-and-coffee