Gotta Catch 'Em All!

Pokemon and 3 Traits that Make for Effective Teachers

I had the pleasure of talking with the recent class of the Harvey Fellows this past week in Berkeley. The Harvey Fellowship provides mentorship and support to cohorts of Christian graduate students in strategic disciplines, studying at elite institutions (Harvard, Stanford, MIT, etc). They tend to be in their 20s or early 30s and are all extraordinarily talented and intelligent. The staff and mentors for the fellowship use the language of calling these fellows to be “co-redeemers with Christ,” a concept that is close to my heart and the mission of Hildegard College as well, as we seek to for redemptive entrepreneurs steeped in the wisdom of the liberal arts tradition.

During my time with the group, I shared a bit about my own story — entering the rat race of academia, soon becoming disillusioned by what industrial higher ed has become, and leaving it to found a college dedicated to mentorship, deep learning, and culture creation.

My argument to them was about the nature of teaching:

“We grow when we love what we’re doing. And we love what we’re doing when we’re doing it alongside others.”

Substitute “learning.” We learn when we love what we’re doing. And we love what we’re doing when we’re doing it alongside others. Relationship is most of the battle, especially in teaching. And that’s not just a pithy adage. It’s the truest thing I know about teaching.

Tongue in cheek, while speaking to the fellows I mentioned a poem that I’d recently heard with my kids and began reciting it:

I wanna be the very best

Like no one ever was.

To catch them is my real test

To train them is my cause.

A moment of silence, and one of the fellows shyly whispered, “Pokemon!”

I kept reading my “poem,” when one of the mentors jumped in and sang the chorus to the original tune:

Gotta catch 'em all--

It's you and me

I know it's my destiny

Ooooh, you're my best friend

In a world we must defend

Pokemon! Gotta catch 'em all--

Our hearts so true

Our courage will pull us through

You teach me and I'll teach you

Pokemon!

Leave it to a 40-year-old art professor wearing a Five Iron Frenzy hoodie to know the lyrics to the chorus.

If in some bizarre reality you’re unfamiliar with Pokemon, it’s a show and card game about humans who train these monstrous little animal-beings called Pokemon — some cute and some grotesque and some industrial. They then battle against other Pokemon “trainers” as their creature companions duke it out using super powers. …As an interesting metaphysical prompt, ask a kid to define a “Pokemon” technically.

My 10-year-old has this habit of rewatching the final episodes of shows he likes over and over again. Pokemon is one of them. And in the series finale (SPOILER ALERT) the main trainer, Ash, battles the world champ, Leon, inside a stadium packed to the brim. And when Ash’s Pokemon, Pikachu, looks to be done and dusted, he/she has a vision of the moment he met Ash and is inspired to reengage the fight with vigor. The theme song kicks in and my son gets pumped!

So many second-hand viewings of this scene have afforded me the opportunity to reflect on the lyrics, and especially the line:

“You teach me and I’ll teach you.”

I’m not just blowing smoke here. There’s a deep philosophy of teaching expressed by this line. In essence, I teach you, but in order to do that, I need to learn from you how to teach you.

In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, the 20th-century Brazilian philosopher, Paulo Freire, contended that truly liberating education requires a reciprocal learning experience for student and teacher alike:

“Education must begin with the solution of the teacher-student contradiction, by reconciling the poles of the contradiction so that both are simultaneously teachers and students.”

The contradiction he’s talking about is the common practice of treating students as if they are less capable than they really are, even less human. Students become what you teach them to become, not just by what you tell them but more so by how you tell them it. If you lecture to students and expect them to rehearse what you’ve said back to you as a measurement that they’ve “learned,” you’re treating them like a computer that downloads information or a bank that you deposit money into. But no good teachers really think they’re students are like this. So, Freire says, teach in such a way that reflects what you believe your students are, as rational beings.

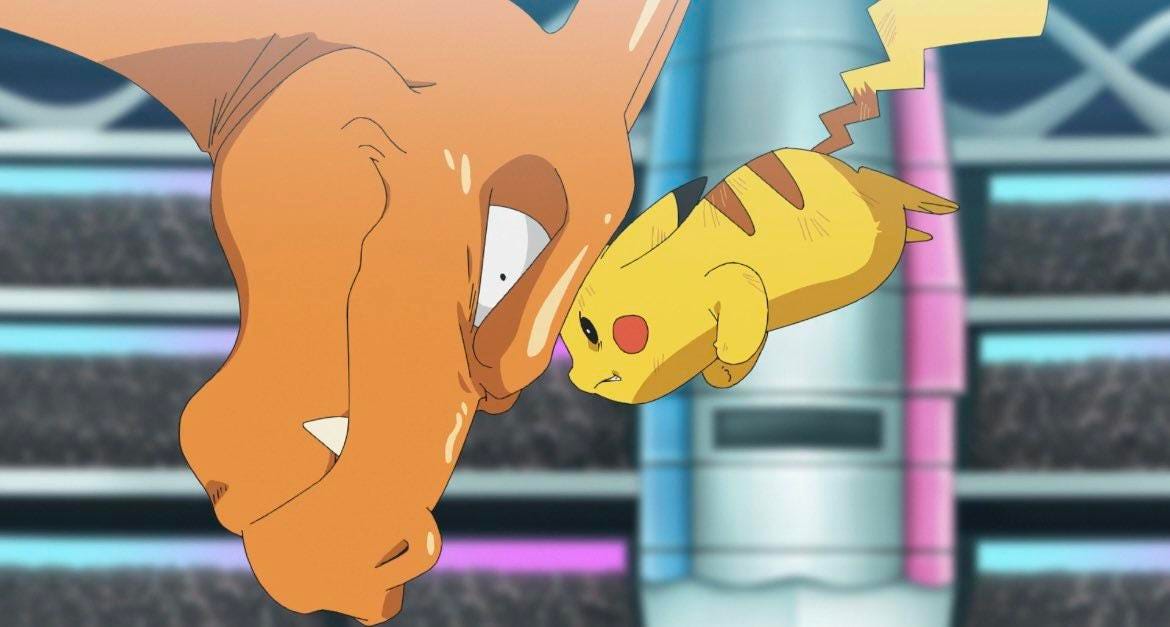

A Pokemon’s power in battle isn’t determined only by their raw ability. It’s derived from the bond formed between the little monster and its trainer. Pikachu is a pudgy yellow ball of electricity. And in the final battle he’s fighting Charizard, perhaps the most epic of all Pokemon.

But it’s the bond between Ash and Pikachu that gives the little rodent the power he needs to win.

Maybe you think I’m making an obvious point. Of course, teachers need to listen to their students, to engage them in conversation, to know where they’re at. But if you look at how the majority of teachers conduct their classrooms, you’d see why it’s a point worth repeating.

Ask a veteran public school teacher about their most cherished teaching experiences. Likely, they’ll recount moments they’ve had with students whom they’ve gotten to know well. They built real relationships, even friendships, with them. What they WON’T tell you about are the awesome lectures they delivered, or how their own deep knowledge of the subject matter made it come alive to students.

3 Attributes of Effective Teachers

For the past several years I’ve helped a behavioral health company conduct and implement research on how to improve counseling and therapy outcomes for clients. Early on, we found that some of the least significant predictors of positive outcomes for people in counseling were the credentials that the counselor or therapist possesses. Also insignificant were the specific methodologies chosen and the years of experience that the provider had. Far and away, the most significant predictor of positive outcomes was what is called the “therapeutic alliance” — essentially, whether the provider and the client get along and like one another.

I believe the same applies to teachers and professors. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen the reverse fallacy in academia! And always in the form of a complaint. A comparatively unagreeable professor complains that students are failing their class, or that enrollment in their courses is low, or that their evaluation scores are below what they need for promotion. So they complain about the process. “Our students aren’t prepared coming into my class!” Or, “our evaluation process is biased!” No, that’s not it. What’s happening is that you’re unpleasant to be around. Students get the feeling that you don’t care about them, much less know them. And so they earn bad grades.

There are 3 attributes near the top of the list of traits that the most effective counselors and therapists possess that equally apply to educators.

Curiosity. I don’t mean fake curiosity but a real interest educators take in their students, their students’ culture and lives. One of my favorite expressions when someone says their bored is to respond that only boring people get bored. In the same way, only uninteresting people struggle to be curious.

Generosity. I use “generosity” instead of “empathy” on purpose, even though the clinical research will say empathy. My problem with empathy is that it requires that you imagine yourself walking in somebody else’s shoes in order to feel for them, as if they’re an alter ego. “Sympathy” is a better word, but in psychology circles, sympathy is considered condescending, as if you’re simply pitying somebody. But it’s more powerful, since to have real sympathy and compassion for someone else without imagining that you yourself were suffering like they are requires you to care for another person for their sake and not for your own. Generosity represents this less controversial form of sympathy.

Confidence. Surprisingly to me when I first learned it, confidence is at the very top of many of the lists of the traits that most powerfully predict positive outcomes for clients of counselors and therapists. Confidence here means telling the truth, or what I like to call “truth talk.” When truth talk is done with generosity and curiosity, it can be an extraordinarily powerful trait for teachers to possess. We should avoid a performative form of confidence and embrace one that is accompanied by humility. Say what you really think, especially when students ask, even if you’re answer is I don’t know.